|

AUTHORITIES IN THE

CATHOLIC CHURCH are not

interested in learning facts about the actual pattern and practice of

celibacy among priests or religious, or among their own ranks for that

matter.[1]

This is as true of Spain as it is in the United States. Bishops are

not interested now and they were not interested in 1990 when I

published my study, A Secret World, or in 1995 when this book

and Sex, Priests, and Power

[2] were published. Even more astonishingly the bishops of the United

States turned their collective thumbs down and noses up at the most

sophisticated evaluation of the crisis of clergy abuse of minors

written specifically as a service to them in 1985[3]. AUTHORITIES IN THE

CATHOLIC CHURCH are not

interested in learning facts about the actual pattern and practice of

celibacy among priests or religious, or among their own ranks for that

matter.[1]

This is as true of Spain as it is in the United States. Bishops are

not interested now and they were not interested in 1990 when I

published my study, A Secret World, or in 1995 when this book

and Sex, Priests, and Power

[2] were published. Even more astonishingly the bishops of the United

States turned their collective thumbs down and noses up at the most

sophisticated evaluation of the crisis of clergy abuse of minors

written specifically as a service to them in 1985[3].

In 1990 an Archbishop wrote after

reading my book ”I would have to say that it (the figures of sexual

activity) certainly corresponds with so much I learned these

twenty-seven years as a Superior.” He went on to say that although he

knew that my book was not anti-celibacy he feared that it would be

perceived as such and further it would be seen as disloyal and

contribute to “a kind of voyeurism about the sex life of clerics.” I

have not found one scholar (or Vatican official) who seriously

disagrees with my conclusion that at any one time no more than 50

percent of clergy are practicing celibacy. That, of course, means that

most priests are sexually active for a part or the whole of their

priesthood. A 2006 report from Brazil also said that 50 percent of the

priests there are not practicing celibacy.

I have not found it necessary to

revise my 1985 estimates of clergy celibate/sexual practice save for

priests who involved themselves with minors (upward to 9 percent), and

homosexual orientation currently to 30-40 percent. Some people raise a

hew and cry over the methodology Rodriguez and I used, (even as they

agree with our figures). No one has presented better figures; none has

come up with any better way to study the actual sexual practice and

behavior of bishops and priests. Rodriquez suffered antagonism, but

not disagreement on his figures.[4]

His work needs to be added to the glossary of the sexual pattern and

practice of men who are presented to the public as sexually abstinent

(celibate).

Current studies about priests use

well established sociologically, random selected clergy population to

study the “happiness” of priests, or the numbers that would still

choose priesthood—“do it again”—or attitudes about sexual issues. But

not one study has attempted to study the pattern and practice of the

sexual lives of priests and bishops.[5]

Sociologists have limited themselves to poles and surveys.

Even the John Jay study of the

Crisis of Sexual Abuse in the United States has only recorded the

priests “reported” for the sexual abuse of minors (now well over 5,000

since 1950) from the data supplied by the various dioceses.[6]

As more cases are documented the actual number of abusing priests is

approaching 10 percent, for instance in Boston and Albany. Los Angeles

had 11.5 percent of its active priests in 1983 subsequently revealed

to be sexual abusers. The Diocese of Tucson harbored 24 percent

abusers on its active clergy rolls in 1988—including retired Bishop

Francis J. Green.

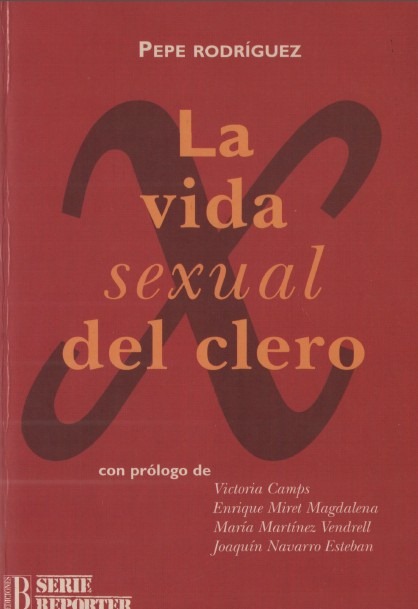

Edouard Del Rey reviewed this

book in December 1995, but it is still available from Amazon.

Rodriguez is a noted investigative journalist who is as interested as

I am in understanding the “deep structures underlying surface

phenomena.” None of this effort can be faulted as being anti-Catholic,

anti-priest, or anti-religion. These are sincere efforts to establish

facts that will aid solid reconfiguration of religious life.

The first part of the book

discusses some theoretical issues that underlie the ecclesiastical

requirement for priests to promise celibacy in order to be ordained to

major orders. He points out what is well known that there is no

biblical foundation for the obligation.

Rodriguez emphasizes the

historical reasoning of celibacy based on economics. He quotes the 451

declaration of the Council of Chalcedon that “no one may be ordained

priest or deacon if the local community has not nominated him” (i.e.

can support him). Lateran III in 1179 likewise dictated that a man

cannot be ordained “if he does not have a benefice that guarantees his

subsistence.” (Celibacy became obligatory for ordination in the Roman

Rite at the II Lateran Council in 1139.) He neglects a good many facts

that would bolster his argument: The Synod of Elvira, 309 specifically

dictates that priests abstain from sex even if they are married and

all of their property should be inherited by the church. Pope Benedict

VIII at the Synod of Pavia in 1122 stripped the wives and concubines

of priests and deacons of all rights and status and decreed that

children of these unions be relegated to serfdom (slaves). Benedict

feared that church property would be dissipated among clerical

offspring; and the ruling became part of the Imperial code.[7]

Rodriguez calls the psychological

consequences of clerical celibacy “enormous.” He puts his finger on

elements that foster and preserve psychosexual immaturity.[8]

The risks begin in the seminary where the structures maintain the risk

of cultivating infantile personalities. The result: “one part of the

clergy loses its ability to become persons with the capacity to love,

to understand, to have happy friendships, to know how to be

affectively close to another person…they are converted into sacred

functionaries, cold, distant, and useless to the communities in which

they live.”

The seminaries in Spain come in

for harsh criticism. (Are they really different in the United States?)

Seminaries do not hesitate to recruit, accept, and ordain men showing

poor psychological equilibrium and lacking common sense. The system

represses independent thought and judgment in favor of obedience to

church dictates. The spirit withers in an atmosphere of rigidity. He

points to Opus Dei as a prominent example of this tradition.

The third problematic area

undermining the integrity of the priesthood is the power and control

that obligatory celibacy imposes. Priests are held in a kind of sexual

bondage in a system of obedience to the bishop. Those who practice

celibacy more rather than less of the time must conform or accommodate

to a system of being ruled in mind and judgment. Others must pretend

to be celibate or risk loosing their social status, their employment,

their benefits, and association with the people they care for and who

care for them. They must sacrifice everything if they blatantly defy

custom. Many are afraid to leave the security of clerical culture.

One chapter is devoted to the

methods bishops use to handle violations of celibacy that cannot avoid

action. The methods are well known to the American public via the

media.[9]

Generally bishops do not conform

to the dictates of Canon law that provide penalties up to suspension

for sexual misconduct by a priest. It is debatable whether Spanish

bishops are more lax than the American hierarchy or whether US bishops

are more adept at denial, delay, deception, and dishonesty when it

comes to sexual malfeasance of priests. Secrecy to avoid scandal is

the gold standard of dealing with sexual problems in both countries.

Priests are transferred from parish to parish, to other dioceses or to

foreign missions (countries) without traceable notice to the receiving

jurisdiction. A significant number of problem priests come to the

United States from many dioceses around the world, not just Spain. The

author claims, however, that bishops are willing to make almost any

accommodation to a sexually active priest in order to keep him in

service to the diocese. He claims that the bishops are lax in

supervision and close their eyes whenever possible.

Rodriguez makes an astute

observation about the bond between a sexually offending priest and his

bishop. The offences and the concomitant guilt bind the priest ever

closer to the system and reinforce his dependency on it. I have found

repeatedly that these conditions frequently pave the way to

promotion and advancement within the system. The dynamic is similar

the workings of gang or cosa nostra-like maneuvers that

produce and reward loyalty by threat of exposure. The secret

transgressions form a bond that makes the man trustworthy.

A conclusion the author draws is

that the church is powerful and largely unassailable. Power and

control are prominent; justice, especially to victims, is tertiary and

avoided wherever possible. Secrecy is sacred.

The second half of the book

records numbers from a two-part study. The first series of figures

deal with the sexual practices generally of active priests:

-

95 percent of priests and

bishops masturbate.

-

60 percent have sexual

relations.

-

26 percent have attachments

to minors.

-

20 percent are involved in

homosexual practices.

-

12 percent are exclusively

homosexual.

-

7 percent are sexually

involved with minors.

These figures are not shockingly

different from those in the United States or in South Africa, or

Brazil. The priesthood is in flux: 20 to 50 percent of priests leave

the ministry worldwide—18.5 percent in Spain. In 1995 the median age

of 33,000 Spanish priests was 60 years.

A second series of figures come

from a group of 354 priests who are sexually active and report on

their sexual activity.

-

53 percent of this group are

sexually active with adult women.

-

21 percent are sexually

active with adult men.

-

14 percent are sexually

active with minor boys.

-

12 percent are sexually

active with minor girls.

-

In all 74 percent are

involved with adults.

-

And 26 percent are involved

with minors.

-

65 percent of priests choose

sexual partners of the opposite sex.

-

35 percent of priests choose

same sex partners.

Rodriguez records the ages at

which the priests became sexually active: only 4 percent became active

before they were 24 years old, that would be prior to ordination. One

quarter started their sexual activities during the first five years

after ordination. But over half of the priests—64 percent—began their

sexual activity after they were 40 years old. These figures are

pregnant with meaning for the study of the priesthood. Masturbation

and other means of solitary satisfaction cannot endure the long

loneliness of ministry. The need for companionship grows more intense

as a man grows older. Sexual abuse of minors on the other hand is

likely to begin in the early years of the ministry

Priests who

have mastered celibacy over the long haul are as secretive about their

processes as those who are sexually active. If priests could only

openly share knowledge and experience of celibacy it would be more

possible for more clergy to be successful and the victims of celibate

failure—girls, boys, women, men, and priests themselves—would be

spared much suffering and hypocrisy.

[1]

The Millenari, The Shroud of Silence: The Story of Corruption

Within the Vatican. (Via col vento in Vaticano. Kaos

editione, Milano: 1999) Translated from the Italian by Ian Martin

and published in Canada by Key Porter Books: 2000. A group of

Vatican officials wrote this book without attribution. The Vatican

condemned the work that became a best seller. It describes various

political and sexual corruptions in Vatican offices.

[2]

A.W.Richard Sipe, A Secret World: Sexuality and the Search for

Celibacy, Brunner/Mazel, New York: 1990. Pp 324. and Sex,

Priests, and Power: Anatomy of a Crisis, Brunner/Mazel, New

York: 1995. Pp. 220.

[3]

Fr. Thomas Doyle, O.P., Ray Mouton, Esq. & Fr. Michael Peterson,

M.D. prepared a confidential report: The problem of Sexual

Molestation by Roman Catholic Clergy: Meeting the Problem in a

Comprehensive and Responsible Manner in 1985 and presented a

copy to every American Bishop. The bishops ignored it, claimed

that they knew everything in it, reviled and repudiated the

authors. Although purloined copies were circulated it was

published for the first time in 2005 as a chapter in Sex,

Priests, and Secret Codes: The Catholic Church’s 2000 Year Paper

Trail of Sexual Abuse. Doyle, Sipe & Wall, Volt Press. Los

Angeles: 2005.

[4]

There was tremendous televised debate between the author, priests,

and members of Opus Dei, but no one has dared to challenge the

reality of the numbers. This has been my experience with my study.

[5]

Andrew Greeley, Priests, A Calling in Crisis, University of

Chicago Press, Chicago: 2004. Pp. 156.

[6]

The John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Report on the Sexual

Abuse Crisis in the Catholic Church, February 27, 2004.

[7]

Sipe, A Secret World, p.44.

[8]

For a comparison to US clergy Cf. Kennedy & Heckler, The

Catholic Priest in the United States: Psychological

Investigations, USCCB, Washington, D.C.: 1972

[9]

The investigative reports of the Spotlight Team of the Boston

Globe in 2002 gained the most widespread attention about clergy

sex abuse in the United States, but Jason Berry wrote about the

problem in 1984 and published Lead Us Not Into Temptation

in 1992. All the reports record similar methods of concealing sex

problems of clergy.

|